Ein Gefängnisgedicht von Paul Verlaine /A Prison Poem by Paul Verlaine

Die Haftstrafe, die Verlaine aufgrund einer tätlichen Auseinandersetzung mit seinem Dichterfreund Arthur Rimbaud verbüßen musste, findet auch in seiner Dichtung ihren Niederschlag. Die äußere wird dabei auch mit einer inneren Gefangenschaft assoziiert.

Der Himmel über dem Haus –

wie ist er so still, so fern aller Hast!

Der Baum, wie schwingt in das Blau hinaus

er selbstgenügsam den Ast!

In unerschütterlicher Sanftmut bebt

herüber des Kirchturms Klang;

und im Gebüsch erinn’rungsschwer webt

ein Vogel klagenden Sang.

Ach, das Leben, das Leben – wie leicht!

Träumend sonnen sich Ähren satt,

indessen die Luft besänftigend streicht

durch das Geraune der Stadt.

Du aber siehst in dem lachenden Tag

traurig sich spiegeln ein andres Gesicht,

ein anderes Land, das im Dunkeln längst lag,

siehst deiner Jugend ungeschriebnes Gedicht.

Paul Verlaine: Le ciel est, par-dessus le toit, … aus: Sagesse (1880). Oeuvres complètes, Bd. 1, S. 272. Paris 1902: Vanier

Der Blick des Gefangenen

Verlaines 1880 erschienener Gedichtband Sagesse lässt sich als dichterische Verarbeitung seiner mehrmonatigen Haftzeit ansehen. Dies spiegelt sich auch in den oben wiedergegebenen Versen wider.

Der Blick des lyrischen Ichs ist hier erkennbar nach außen gerichtet. Man kann sich gut vorstellen, wie hier jemand durch die Gitterstäbe seiner Zelle ins Freie schaut und von jenem ungebundenen Leben träumt, das ihm im Gefängnis verwehrt ist. Die herausgehobene Stellung von Himmel und Kirchturm in dem Gedicht verweist zudem auf den Halt, den Verlaine während seiner Haftzeit durch den christlichen Glauben erfahren hat.

Die Welt jenseits der Gitterstäbe des eigenen Ichs

Außer auf die äußere verweist das Gedicht allerdings auch auf eine innere Gefangenschaft. Diese ist nicht durch ein Gericht verfügt, sondern ergibt sich aus den Lebensumständen und der Art und Weise, wie die konkrete Person mit diesen umgeht.

So deutet der Schluss des Gedichts den Gedanken an, dass sich das eigene Leben auch ganz anders hätte entwickeln können; dass bei den in der Jugend aufgegangenen Keimen auch eine ganz andere Auswahl hätte getroffen werden können; dass andere Keime gepflegt und dadurch die gesamte innere und äußere Entwicklung einen ganz anderen Verlauf hätte nehmen können.

Die Verse zeichnen damit das Porträt eines Menschen, der in den Käfig seines eigenen Lebens eingesperrt ist: Draußen, jenseits der Gitterstäbe seines Ichs, sieht er die Schönheit des Lebens, die Leichtigkeit, mit der andere sich daran freuen, den Halt des Kirchturms. Dieser kann dabei außer auf den christlichen Glauben auch allgemein auf den „Leuchtturm“ fester innerer Überzeugungen bezogen werden.

Die in dieses Leben hinausträumende Person aber bleibt eingesperrt in sich selbst. Die Welt jenseits des Käfigs ihres Ichs ist unerreichbar für sie.

Die existenzielle Ebene: Das Gefängnis der „condition humaine“

Wie das Gedicht Gaspard Hauser chante (Kaspar Hauser singt) sind auch die hier diskutierten Verse erkennbar von der Kaspar-Hauser-Thematik gefärbt. In Verlaines Gedichtband Sagesse finden sie sich denn auch im unmittelbaren Umfeld dieses Gedichts.

Wie Verlaines Kaspar-Hauser-Gedicht können die Verse damit als Verweis auf das Gefühl einer grundsätzlichen Fremdheit in der Welt verstanden werden. Dies lässt sich zwar auch auf die Biographie Verlaines beziehen, weist zugleich aber über diese hinaus. Gleiches gilt für das in dem Gedicht thematisierte Gefühl, an irgendeiner Stelle des eigenen Lebens falsch abgebogen zu sein, das ebenfalls nicht wenigen Menschen bekannt vorkommen dürfte.

Dabei darf allerdings nicht vergessen werden, dass die Kluft zwischen einem als dissonant empfundenen Leben und einer erträumten vollkommenen Harmonie keineswegs immer in uns selbst begründet ist. Vielmehr kann ein glückliches Leben uns auch aus objektiven Gründen verwehrt sein.

Dies gilt zunächst, in einem existenziellen Sinn, für das menschliche Dasein an sich, das in seinem Zum-Tode-Sein strukturell von der absoluten Vollkommenheit abgeschnitten bleibt. Daneben können aber auch materielle Not, sozialer Ausschluss oder Formen eines kulturellen Unbehaustseins dazu führen, dass ein erfülltes Leben für die Betreffenden ein unerfüllbarer Traum bleibt.

Es ist deshalb vielleicht auch kein Zufall, dass eine der wohl gelungensten Vertonungen des Gedichts von einer jüdischen Künstlerin (Catherine Stora) stammt. Dies ist umso bemerkenswerter, als auch das Gedicht Gaspard Hauser chante in Georges Moustaki einen Interpreten mit jüdischen Wurzeln gefunden hat. Es hat eben kaum ein Volk die eigene Fremdheit in der Welt im Verlauf seiner langen Geschichte so stark erfahren wie das jüdische.

Catherine Stora: Le ciel est, par dessus le toit …; Live-Aufnahme aus dem Jerusalemer Khan-Theater, 16. Juni 2016; Violincello: Hannah Blachmann

Zu dem Gedicht Gaspard Hauser chante (Kaspar Hauser singt) vgl. den Post Die Fremdheit der Welt.

English Version

The Cage of One’s Own Life

A Prison Poem by Paul Verlaine

The imprisonment imposed on Verlaine for an assault on his fellow poet Arthur Rimbaud is also reflected in his poetry. Here, the outer imprisonment is associated with an inner imprisonment.

The sky above the house –

how tranquil it is, how pure!

The tree, how gracefully it sways

its branches in the immaculate azure!

The ringing of the church bells

floats comfortingly through the air.

And in the bushes a bird

weaves a song full of memories.

Ah, life, life – how gentle it can be!

Dreaming, the ears of corn bask in the sun,

while the air strokes soothingly

through the murmur of the town.

But you hear in the laughing day

the gloomy echo of another laughter,

you see another land, long since a prey to oblivion:

your youth’s unwritten poem.

Paul Verlaine: Le ciel est, par-dessus le toit, …from: Sagesse (Wisdom; 1880). Oeuvres complètes, Vol. 1, p. 272. Paris 1902: Vanier

The Gaze of the Prisoner

Verlaine’s poetry collection Sagesse, published in 1880, can be seen as a poetic reflection of his months in prison. A echo of this can also be found in the verses reproduced above.

The gaze of the lyrical I is clearly directed outwards here. We can well imagine someone looking through the bars of his cell into the world and dreaming of the unbound life he is deprived of in prison. In addition, the prominent position of the sky and the church tower in the poem refers to the support of Christian faith that Verlaine experienced during his time in prison.

The World Beyond the Bars of One’s Own Ego

Apart from the external imprisonment, however, the poem also refers to an internal imprisonment – an imprisonment that is not imposed on the respective person by a court, but results from the circumstances of life and the way this person deals with them.

Accordingly, the final verses of the poem suggest that one’s own life could also have developed in a completely different way; that a completely different choice could have been made among the germs that sprouted in youth; that other germs could have been nurtured, giving the entire inner and outer development a completely different direction.

The verses thus paint the portrait of a person who is locked in the cage of his own life: outside, beyond the bars of his ego, he sees the beauty of life, the effortlessness with which others rejoice in it, the anchor of the steeple – which, apart from the Christian faith, can also be generally associated with the „lighthouse“ of firm inner convictions.

The person daydreaming of this life, however, remains imprisoned within himself. The world beyond the cage of his ego is inaccessible to him.

The Existential Level: The Prison of the „Condition Humaine“

Like the poem Gaspard Hauser chante (Kaspar Hauser sings), the verses discussed here are also noticeably coloured by the Kaspar Hauser topic. Consequently, they are placed in immediate vicinity of this poem in Verlaine’s poetry collection Sagesse.

Like Verlaine’s Kaspar Hauser poem, the verses point to the feeling of a fundamental strangeness in the world. While this can of course be related to Verlaine’s biography, it also has a more general meaning. The same applies to the feeling of having taken a wrong turn at some point in one’s life, which is probably also familiar to quite a few people.

In this context, however, we must not forget that the gap between a life perceived as dissonant and the utopia of a life in perfect harmony is by no means necessarily rooted in ourselves. Rather, we can also be cut off from a fulfilled life for objective reasons.

This applies first of all to human existence itself, which in its condemnation to death remains excluded from absolute perfection. In addition, however, material hardship, social exclusion or forms of cultural homelessness can make a fulfilled life an unattainable dream for those concerned.

It is therefore perhaps no coincidence that a particularly congenial setting of the poem was composed by a Jewish artist (Catherine Stora). This is all the more remarkable because the poem Gaspard Hauser chante was also set to music by a singer with Jewish roots (Georges Moustaki). The reason for this might be that hardly any other people has experienced its own foreignness in the world as strongly as the Jewish people in the course of its long history.

Catherine Stora: Le ciel est, par dessus le toit …; Live recording from Jerusalem’s Khan Theatre, June 16, 2016; violincello: Hannah Blachmann

For the poem Gaspard Hauser chante (Kaspar Hauser sings), see the post The Strangeness of the World.

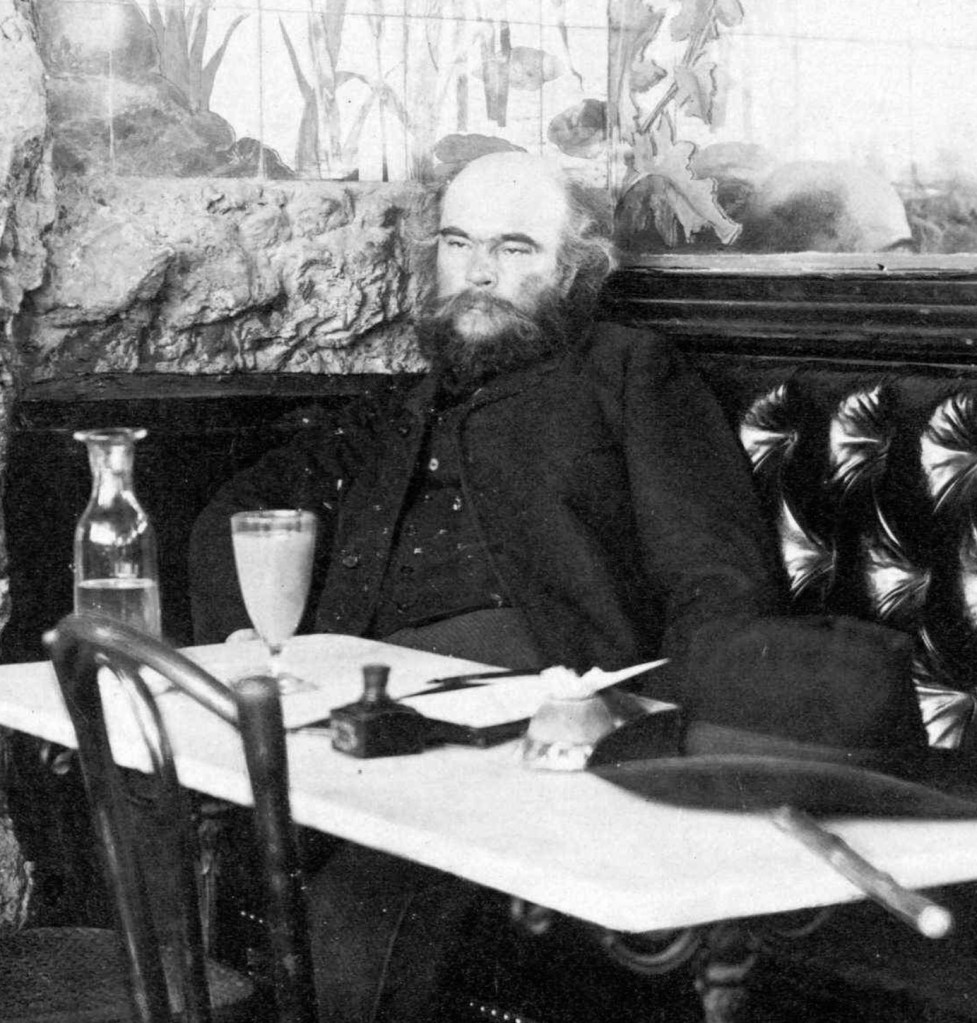

Bilder / Images: Hendrik Frans Schaefels (1827 – 1904): Junger Gefangener in seiner Zelle / Young prisoner in his cell. Wikimedia commons ; Paul Marsan Dornac (1858 – 1941): Foto von Verlaine im Café François 1er, Mai 1892 / Photo of Verlaine in the Café François 1er, May 1892(Wikimedia commons