Paul Verlaines Gedicht Soleils couchants (Sonnenuntergänge) / Paul Verlaine’s Poem Soleils couchants (Sunsets)

Paul Verlaine sah die Poesie als eine eigene Welt, die ihren Sinn aus sich selbst generiert. Ein wichtiger Aspekt war für ihn dabei die Musikalität der Dichtung.

Sonnenuntergänge

Ein schwacher Dämmerschimmer gießt

über das dunstverhangene Feld

die Schwermut, die purpurn umfließt

am Abend die Welt.

Das Schiff der Schwermut entführt

mit sanften Wiegegesängen

mein Herz, das so sich verliert

im Traum von Sonnenuntergängen.

Und fremde Gesichte, weit

wie die zerfließende Glut

über des Meeres Unendlichkeit,

Gespenster aus purpurnem Blut,

ziehen vorbei, ein endlos‘ Geleit,

ziehen vorbei, ganz wie die Glut,

wie die zerfließende Glut

über des Meeres Unendlichkeit.

Paul Verlaine: Soleils couchants aus: Poèmes saturniens (1866).Oeuvres complètes, Bd. 1, S. 26 f. Paris 1902: Vanier

Vertonung von Léo Ferré: Soleils couchants aus: Léo Ferré chante Verlaine et Rimbaud (1964)

Ein musikalisches Gedicht

„De la musique avant toute chose“ – vor allem muss es musikalisch sein. Dies ist der Leitgedanke der Lyrik Paul Verlaines, den er denn auch an den Anfang seines programmatischen Gedichts Art poétique (Die Dichtkunst) stellte [1].

Diese besondere Musikalität der Dichtung spiegelt sich auch in seinem Gedicht Sonnenuntergänge wider. Der entscheidende musikalische Effekt ergibt sich dabei aus dem Wechsel zwischen hellen und dunklen Vokalen in den Reimen. Dadurch erzeugen die Verse eine Art Zwischenwelt, in denen Dur- und Molltöne zu einem neuen Klangraum zusammenfließen.

Die Eigenständigkeit der Klangwelt entspricht dabei Verlaines Überzeugung von einer Eigenweltlichkeit der Dichtung. Die Musikalität der Dichtung ist damit kein Selbstzweck. Vielmehr dient sie dazu, dichterische Stimmungen unabhängig von den sprachlich vorgeprägten Deutungs- und Erfahrungsmustern wiederzugeben.

Eingeschränktes Bekenntnis zum Reim

Verlaines Verhältnis zum Reim ist ambivalent. Auf den ersten Blick scheint der Zwang zum Reim der Vorstellung einer Dichtung, die sich von vorgegebenen sprachlichen Mustern und dem Korsett strenger Formen lösen möchte, zu widersprechen. Er erscheint aus dieser Perspektive als unnötige Fessel, die neuartigen dichterischen Klängen eher im Wege steht. Folgerichtig verhöhnt Verlaine den Reim in seiner Art poétique auch als Erfindung eines „tauben Kindes“ [2].

Nichtsdestotrotz hält Verlaine den Reim in einer Dichtung, die eine Musikalität im oben beschriebenen Sinn anstrebt, für unverzichtbar. Er plädiert allerdings für einen „Rime assagie“, also einen „weiseren“, bewussteren und kontrollierteren Einsatz des Reimes. Denn „wohin führt es wohl, wenn wir ihn nicht überwachen?“ [3]

Ähnlich hat sich Verlaine 1888 in dem Essay Un mot sur la rime (Ein Wort über den Reim) geäußert. Darin betont er, nicht der Reim selbst sei „verdammenswert“, sondern lediglich seine missbräuchliche Verwendung. Deshalb ganz auf ihn zu verzichten, sei jedoch auch nicht empfehlenswert, da „unsere wenig akzentuierte Sprache“ ohne ihn keine Dichtung hervorbringen könne [4].

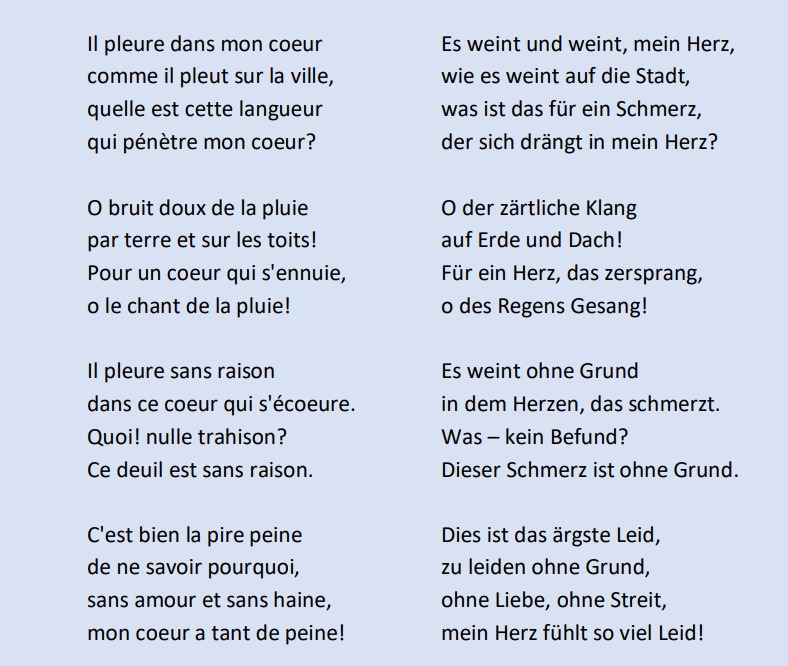

Il pleure dans mon cœur …

Zum Abschluss sei an dieser Stelle noch auf jenes Gedicht hingewiesen, das oft als typisches Beispiel für Verlaines musikalisches Dichtungsideals angeführt wird. Darin verknüpft der Dichter die Monotonie des rauschenden Regens mit der melancholischen Gestimmtheit des lyrischen Ichs.

Ganz im Sinne der postulierten musikalischen Dichtung tritt hier die konkrete Bedeutung der einzelnen Worte zurück hinter der besonderen Harmonie, die durch Rhythmus, Assonanzen und Reime erzeugt wird. Die sprachliche Welt wird so durch einen eigenen Klangraum transzendiert, durch den sich die Dichtung jener gegenüber in ihrer Autonomie behauptet:

(aus: Romances sans paroles, 1874; Oeuvres complètes, Bd. 1, S. 155 f. Paris 1902: Vanier)

Nachweise

[1] Paul Verlaine: Art poétique (1874); Erstveröffentlichung in Paris Moderne (1882); in einer Gedichtsammlung Verlaines zuerst in Jadis et naguère, (1884); hier zit. nach Oeuvres complètes, Bd. 1, S. 311 f. Paris 1902: Vanier.

[2] Ebd., S. 312.

[3] „Si l’on n’y veille, elle ira jusqu’où?“ (ebd.)

[4] Paul Verlaine:Un mot sur la rime; Erstveröffentlichung in Le Décadent (1888); hier zit. nach Oeuvres posthumes, Bd. 2, S. 281 – 288 (hier S. 281). Paris 1913: Messein.

English Version

The Music of Poetry

Paul Verlaine’s Poem Soleils couchants (Sunsets)

Paul Verlaine saw poetry as a world of its own that generates its meaning from itself. In this context, the musicality of poetry was crucial to him.

Sunsets

A faint twilight glow pours

over the mist robe of the field

the sorrow that flows as a purple wave

over the world in the evening.

With gentle lullabies, the ship of melancholy

carries away my heart

that loses itself dreaming

in the weightless dances of sunsets.

And strange visions, far away

like the melting embers

over the ocean’s infinity,

spectres of crimson blood,

pass by, an endless procession,

pass by, like the glowing embers,

like the drowning embers

in the ocean’s infinity.

Paul Verlaine: Soleils couchants from: Poèmes saturniens (1866).Oeuvres complètes, Vol. 1, p. 26 f. Paris 1902: Vanier

Musical setting by Léo Ferré: Soleils couchants from: Léo Ferré chante Verlaine et Rimbaud (1964)

A Musical Poem

„De la musique avant toute chose“ – above all, it must be musical. This is the guiding principle of Paul Verlaine’s poetry, which he consequently placed at the beginning of his programmatic poem Art poétique (The Art of Poetry) [1].

This special musicality of poetry is also reflected in his poem Sunsets. The musical effect here results mainly from the alternation between light and dark vowels in the rhymes. In this way, the verses create a kind of in-between world in which major and minor tones flow together to form a new sound space.

The independence of the sound world corresponds to Verlaine’s conviction that poetry constitutes a world of its own. The musicality of poetry is thus not an end in itself. Rather, it serves to reproduce poetic moods independently of linguistically predetermined patterns of meaning and experience.

Restricted Commitment to Rhyme

Verlaine’s attitude to rhyme is ambivalent. At first glance, the compulsion to rhyme seems to contradict the idea of a poetry that wants to break free from predetermined linguistic patterns and the corset of rigid poetic forms. From this perspective, rhyme appears as an unnecessary fetter that stands in the way of new kinds of poetic sounds. Consequently, Verlaine also derides rhyme in his Art poétique as the invention of a „deaf child“ [2].

Nevertheless, Verlaine considers rhyme indispensable in a poetry that strives for musicality in the sense described above. However, he pleads for a „Rime assagie“, i.e. a „wiser“, more conscious use of rhyme. For „where do you think it will lead us if we do not keep it under control?“ [3]

A similar view was expressed by Verlaine in 1888 in the essay Un mot sur la rime (A Note on the Rhyme). In it, he stresses that it is not rhyme itself that is „condemnable“, but only its misuse. However, Verlaine doesn’t recommend abandoning rhyme because of this altogether, since „our poorly accentuated language“ would make it difficult to create poetry without it [4].

Il pleure dans mon cœur …

Finally, the poem that is often cited as a typical example of Verlaine’s musical poetic ideal should be mentioned here. In this poem, the author links the monotony of the rushing rain with the melancholy mood of the lyrical self.

In keeping with the postulated musical poetry, the concrete meaning of the individual words takes a back seat to the special harmony created by rhythm, assonances and rhymes. The world of language is thus transcended by a special poetic sound space, through which poetry asserts its autonomy over that world:

(from: Romances sans paroles, 1874; Oeuvres complètes, Vol. 1, p. 155 f. Paris 1902: Vanier)

* „Peine“ can also mean punishment/sentence in French.

References

[1] Paul Verlaine: Art poétique (1874); first published in Paris Moderne (1882); in a poetry collection by Verlaine first in Jadis et naguère, (1884); here quoted after Oeuvres complètes, Vol. 1, p. 311 f. (here p. 311). Paris 1902: Vanier.

[2] Ibid., p. 312.

[3] „Si l’on n’y veille, elle ira jusqu’où?“ (ibid.)

[4] Paul Verlaine: Un mot sur la rime [A Note on the Rhyme]; first published in Le Décadent (1888); here quoted after Oeuvres posthumes, Vol. 2, p. 281 – 288 (here p. 281). Paris 1913: Messein.

Bilder / Images: Apollo mit Leier; Freskenfragment aus der Umgebung des Augustushauses / Apollo with lyre, fresco fragment from the vicinity of Augustus house; Rom, Museo Palatino; Foto von Carole Raddato (Wikimedia commons); Frédéric Bazille (1841 – 1870): Porträt von Paul Verlaine als Trobadour/ Portrait of Paul Verlaine as a troubadour (1868); Dallas/Texas, Museum of Art (Wikimedia commons); Frederick Childe Hassam (1859 – 1935): Segelboot auf dem Meer bei Sonnenuntergang / Sailing boat on the sea at sunset (Wikimedia commons)

Pingback: Die Musik der Poesie / The Music of Poetry – freudeautor, freudebuchautor, lyrikfreude, dichterfreude